以下、6年以上前のThe New Yorker (September 18, 2012)より。

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/dreaming-of-a-white-president

バラク・オバマが再選勝利を果たした2012年のアメリカ合州国大統領選。

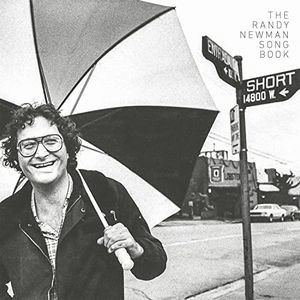

Randy Newmanは、"I'm Dreaming”という新曲をYouTubeに発表した。

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mW7IF8hZ-LA

ランディ・ニューマンは、白人大統領を期待する人種差別主義者に成り代わって歌っている。

以下は、そのときのThe New Yorkerの記事。"Rednecks"など、昔の唄も紹介している。

Culture Desk

Dreaming of a White PresidentBy Ian Crouch

September 18, 2012

In a campaign season that has recently come under the powerful sway of the Internet video, another entry—more subtle than “Innocence of Muslims” and certainly more “elegantly stated” than Mitt Romney’s disdain for the “forty-seven per cent”—has joined the fray. This week, Randy Newman released “I’m Dreaming,” a free song and accompanying YouTube video, that is built around the heavily ironized refrain: “I’m dreaming of a white President, just like the ones we’ve always had….” Newman’s song is not likely to touch off riots or shift the direction of the Presidential campaign, yet it should stir up raw emotions and divergent responses, and reaffirms Newman’s place as one of our most incisive and essential satirists.

Newman’s power as a songwriter has always derived from the massive dissonance between his music and his lyrics. In this case, you don’t expect a charming piano ditty—one that alludes to Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas”—to openly espouse the normally masked feelings of American reality: fear, crass self-interest, proud ignorance, bigotry. And political songs are rarely so verbally dexterous and funny, even if you are as likely to squirm as chuckle when Newman, in his elegant and wry voice, sings: “He won’t be the brightest, perhaps / but he’ll be the whitest / and I’ll vote for that.”

Good satire is bound to upset people, and truly great satire is bound to upset everyone. Take a look at the YouTube comments on the video above to see the full range of reaction to Newman’s latest: self-satisfied “I get it” boasts; derisive “It’s a joke, idiots” attacks; confusion; anger. Few partisan writers (Newman is an Obama supporter) are so generous to their straw men—even here, the narrator of “I’m Dreaming” tries to sort out his feelings of white goodness and black badness. He is simple, but not clueless. One of the nervous-making elements of Newman’s music is that, as he gives his blowhard narrators their due, he also seems poised to make fools out of his listeners and their pat and confident views. That is never clearer than in Newman’s most forceful political song, “Rednecks,” from the masterful 1974 album “Good Old Boys”:

“Rednecks” is told from the perspective of a southern man who is disgusted by watching the Georgia governor Lester Maddox be ridiculed on television by “some smart-ass New York Jew” (reportedly an allusion to Dick Cavett, who is not Jewish, but still), and remarks that “he may be a fool, but he’s our fool,” and decides to sit down and write an ironic ode to his proud, if wayward, homeland. For the first two verses, the narrator lays out a set of familiar characters—twangy, drunken men, “no-necked oilmen from Texas,” and “college men from L.S.U.” who “went in dumb, come out dumb, too”—and backs it with the chorus, “We’re rednecks, rednecks / We don’t know our ass from a hole in the ground. / We’re rednecks, we’re rednecks / We’re keeping the niggers down.” Then the song turns, and the narrator notes that blacks in the North don’t have it much better, that they are “free to be put in a cage,” in Harlem, the South Side of Chicago, and Roxbury. At the end, the chorus comes in again, and suddenly all of us, North and South, are the rednecks.

Newman and the narrator both live in this song, and so we get an inseparable blend of sarcasm, defensiveness, and critique from competing voices: one that disdains the South for its backwardness, another that rips the North for its hypocrisy, and a united voice that loves and loathes the whole mess of shame, arrogance, hatred, and dogged perseverance that is our American inheritance. The song feels silly and devastating all at once.

“I’m Dreaming” is less nuanced in its politics, and doesn’t give voice to as complex and rich a character, but it fits into Newman’s songbook of first-person songs that make you wince while humming along. “Short People” is entirely dedicated to the mock degradation of the little: “They got grubby little fingers / and dirty little minds.” “Political Science” casts America as a sad, lonely little country unfairly hated by everyone else, which would be better off just to “drop the big one.” Even “I Love L.A.,” which sounds as though it might have been commissioned by the city’s chamber of commerce, slips in a subversive gem: “Look at that mountain. / Look at those trees. / Look at that bum over there, man. / He’s down on his knees.” It is a profoundly destabilizing experience to find yourself singing lines like, “We’re keeping the niggers down” in the shower. But the song is dangerously catchy, and that’s part of the point. Racism is insidious—it was in 1974 and it is now—and racism lives in the collective American mind a lot like a pop song does.

Ian Crouch is a contributing writer and producer for newyorker.com. He lives in Maine.

以下、フリーダウンロードのできるサイト。

www.randynewman.com